Picking right back up where we left off, we’re going to discuss zeroing your rifle and holds. Most shooters think they understand the zeroing process, but typically all they know is how to sight in their rifle at a prescribed distance. They’re then told where to hold at known distances. Given, this is all that is needed to shoot, practically speaking. However, I think gaining some knowledge about what a zero does is critical. It’s one thing to just do something. It’s another thing to understand what you’re doing.

To start, zeroing a rifle means sighting it in at a distance. For example, if you sight in your rifle at 100 yards, then that means your shots will impact exactly where you’re aiming at 100 yards. This seems pretty simple, but what if you’re shooting at 50 yards or 273 yards? At 50 yards your point of impact, relative to your point of aim, will be low. At 273 yards, your point of impact, relative to your point of aim, will be low. This may not seem straightforward at first.

When beginners imagine a bullet leaving a barrel, they think of it like a laser beam. They think the bullet exits the barrel and shoots toward the target in a perfectly straight line. The problem with that is gravity. The moment the bullet exits that barrel it wants to come back down to Earth. To compensate for this, sighting systems can’t work linearly, they have to work parabolically, or like an arc. If you can imagine the way you throw a baseball this makes sense. If you want to throw it really far, then you have to aim up to compensate for gravity wanting to bring it back down. If you throw a baseball really hard in a straight line, it won’t go as far as it would if you gave it an arc. Is this starting to make sense?

Bullet trajectories sort of work the same way as throwing a baseball. Up close, you can get away with throwing it straight, but if you want to throw it further then more arc is needed. Since we know now that trajectories have an arc, we also know that that on both sides of that arc the bullet will have the same point of impact, relative to your point of aim. In this case, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Toward the top of the picture, you can see the effect gravity has on a bullet once it exits the barrel. It immediately wants to be pulled back to Earth. As the velocity of the bullet increases it will go further before succumbing to gravity’s effect, resulting in a flatter trajectory. This is why handgun rounds won’t go nearly as far as rifle rounds without having a crazy, almost mortar-like trajectory because you’re having to holdover and create such an insane arc to make up for the lack of velocity.

The bottom of the picture is a demonstration of what a rifle zero does. In this case, it’s an over-exaggerated and poor rendition of a 50 yard zero for an M16. The rifle is sighted in at 50 yards. If you aim at anything at 50 yards the bullet will go exactly where you aim. As you can see from the arc, if you aim at anything past that, then the bullet’s impact, relative to your point of aim will be high. The bullet’s impact reaches its all time high, relative to your aim, at 100 yards. However, past 100 yards the point of impact, relative to your aim, starts to level out and go down again. At 200 yards, the point of aim matches the point of impact just like at 50 yards. What’s really cool is this means that at 200 yards you won’t have to adjust your aim at all and treat it just like the 50! This is the nature of arcs and gravity. What goes up must come down. At any given point on that arc there is an identical point of aim relative to point of impact on the opposite side. The green line striking through the 50 and 200-yard points demonstrates this.

You might be asking yourself, why not just make adjustments to the sights as I go? If I shoot at 50, I’ll adjust the sights to 50. If I shoot at 300, I’ll just adjust the sights to 300, right? This works. In fact, this is how snipers use their precision rifles because it’s more accurate. They have DOPE (Data of Previous Engagements) books and ballistic calculators full of data that tell them exactly how to adjust their scopes based on distance, elevation, humidity, barometric pressure, high-angle shooting, and the list goes on, especially for extreme distances. However, this is very impractical for the purposes of a regular rifle or carbine. The distances you’re likely to use these types of general-purpose rifles are about 300 yards and in, practically speaking. They can certainly be pushed further and are routinely, but some real limitations regarding kinetic energy and lethality start to come into play. The reality is, within 300 yards, you won’t have time to make adjustments to your rifle while you’re getting shot at. Most modern urban engagements are considerably closer than that too, which just compounds the issue. It’s much quicker to memorize a couple of holds and adjust your point of aim on the fly. This is why you zero a rifle at one distance and memorize basic holds. It’s simply faster. It isn’t as precise, but if you become proficient enough you can be extremely lethal and perform at a standard well past the necessities of combat accuracy. I routinely engage 4 targets about the size of a plate carrier, ranging from 50 to 300 yards, in about 10 seconds. And to be frank, I consider myself slightly above an average shooter. There are much better shooters and anyone can learn this. This even applies to hunting. Sometimes you have to make quick shots before the animal leaves your view or gets spooked off. You need to be quick, decisive, and intimately familiar with your weapon.

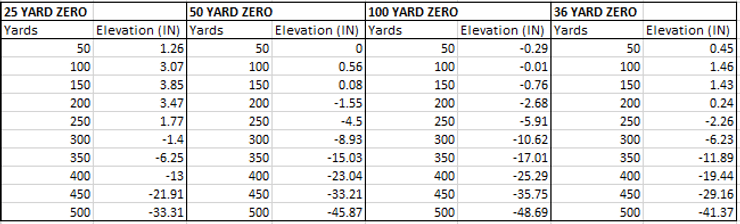

So now you understand that zeroing a rifle is essentially making it shoot in an arc. The next step in the process is determining what distance you should zero it at. Whatever it is, it needs to capitalize on giving you the flattest trajectory so you can have predictable holds. This is largely subjective to you. It’s determined by a number of factors, but the biggest ones to consider are caliber, barrel length, and most importantly, application of the rifle. Considering one of the most common rifles in the United States today is the AR-15, I’ll use it as an example. Personally, I prefer to use the 50 yard zero for it. You can see why in the chart below:

As you can see, with a 50 yard zero I essentially don’t have to change my point of aim until after 200 yards. From 50 yards to 200 yards it’s an extremely simple process: point at the target and pull the trigger. At 300 yards, I hold about 9 inches high. That’s my only hold I have to know with this zero. If I wanted to make it even simpler, all I would have to tell someone is to aim right below the chest from 0-300 yards and they’ll hit the target every single time, and this is on a reduced size target.

You can see that there are other zeroing options, such as the 100 yard zero. It’s my second favorite, but I still prefer the 50 based on my own experience. The 25 meter/yard zero is for the Army and the 36 yard zero is for the Marine Corps. Unsurprisingly, they’re total clusterfucks with rounds impacting above AND below the line of sight drastically. I could give you the history about why the military uses these zeros and a lesson on the typical bureaucratic inefficiencies that plague anything government-related, but just take my word for it. Don’t use a 25 or 36 yard zero just because “the military does it.”

There are some things that need to be addressed when looking at this chart data, however. It was done with an online ballistic calculator. While they can get pretty close, they’re not exactly correct because there are entirely too many factors that reality brings to the table. A theoretical calculator in a vacuum with set of assumptions can’t precisely predict the way your rifle will shoot. They’re a great place to start so you can get a feel for what will be the flattest zero for your rifle, but every rifle is a little different. The only way for you to determine your zero and your holds is to go out and shoot. As an example, for my rifle that’s zeroed at 50 yards, I can tell you that at 100 yards the bullets impact about 1.5” high, at 200 they’re about 2” low, and at 300 it’s about 4-5” low. Practically speaking, there isn’t a significant variation from what the chart says, so I won’t have to alter any of my holds. Just know that ballistic calculators aren’t exact.

We’ve covered zeros and holds from 50 to 300 yards, but what if you need to shoot closer? Statistically speaking, you will. Most engagements now are CQB (Close Quarters Battle) distances. As a civilian or law enforcement officer, you’re far more likely to take a shot inside a structure or around a vehicle. You’re talking about 25 yards and in kind of shots. From 20 to 25 yards you’ll probably have to aim a tad higher. This will be determined by your rifle zero and you’ll just have to test it out. 15 yards and in, or inside a house, is easy. At close distances like this, it won’t really matter what your zero is. The distance is so close that the bullet basically acts like a laser beam like we talked about above. The only thing you’ll have to account for is the height of your sights over your bore, meaning how high they sit over your muzzle. For me, it’s about 3”. So, I know if I need to make a headshot within a house then I’ll need to aim at the scalp.

That’s basically the meat and potatoes of zeroing and knowing your holds. There’s one thing left to consider on the topic and that’s ammunition selection, but that will be discussed on a further blog.

Solid work. Given the popularity of LPVOs it’s also worth reading the scope manual… ELCAN is zeroed at 100m, Athlon LPVOs state BDC works with 50y zero… So if you’re running an LPVO with a BDC reticle, probably should zero using scope requirements to start. As an example, Athlon 1-8x says BDC set for 69g SMK and 50y zero… but that only works with 18″ barrel, a 14.5″ requires considerable holdover to use BDC, tested with 69g SMKs. If LPVO has moa/mrad reticle w/o BDC then zero options are open. Keep up the good work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Excellent points. That reason was actually why I chose the Viper with a general MRAD reticle. I was really conflicted on whether or not to include LPVO’s on this but opted out to stay concise. I wrote another post about LPVO’s after this. Maybe it’ll get resurrected here.

LikeLike

On the Marine Corps and 36 yard zeros. It’s kind of not a 36 yard zero. We conduct an initial zero at 36 yards using the 300m post on the BDC of the ACOG. Once on, we then move back to 100m and refine the zero at 100m using the tip of the chevron/center of horseshoe (depending on RCO vs SDO), which is the 100m aiming point. So, in actuality, the USMC 36 yard zero is a short range sight adjustment with a deliberate offset and a refinement at the zero distance. A more regimented zeroing process than what a lot of people do when they get on paper 2 inches low before punching out to the desired zero distance.

LikeLike

Thanks for the input. Do you still use that SOP for irons though? The Army uses a similar process for the ACOG as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To be honest, I can’t remember for sure. Outside of M16A2s, I think the only time I zeroed BUIS was when my ACOG broke right before a range. At that point, I just did the 36-confirm/refine-at-100 that everybody else was doing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article with great info.

I may steal your illustration on how gravity affects trajectory, compared to a 50 yard zero.

I believe you may have gotten one tidbit mixed up.

“ For example, if you sight in your rifle at 100 yards, then that means your shots will impact exactly where you’re aiming at 100 yards. This seems pretty simple, but what if you’re shooting at 50 yards or 273 yards? At 50 yards your point of impact, relative to your point of aim, will be HIGH. At 273 yards, your point of impact, relative to your point of aim, will be low. This may not seem straightforward at first.”

That sentence should read

“At 50 yards your point of impact, relative to your point of aim, will be LOW.”

All impacts before or after 100 yards with a hundred yard zero will be low.

It’s one of the advantages of a 100 yard zero.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Feel free to steal, just let the people know where you found it! Thanks for coming over from Scattered Shots.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for catching that brain fart! I’ve corrected this now. Glad you got something out of it.

LikeLiked by 1 person